Day 122

We spent the morning packing, going through everything, throwing junk out, going through our clothes and finding that numerous of them didn’t fit. Our hostess, Sophie, said that we could leave all the clothes and car seats behind and she would get rid of them for us. Mom spent the morning going through the big red hold bag packing souvenirs and the overflow from our carry-on bags for the trip home. When we had left home back in September of 2015 we had stuffed every available crevice with bags of dried apples; they were long since gone, and ditching the two booster seats left a considerable cavern in the bag. In retrospect we wished we had picked up a few more souvenirs. Dad worked all morning and by lunch we were ready to eat.

After lunch Mom wanted to walk to the Louis Braille museum just down the hill. When we got there we walked in and an older gentleman welcomed us. One could easily discern that he loved his job. While he readily spoke English it was with a heavy accent making him a bit hard to understand. Mom thought he was the most Dickens-esque character she had ever met. Everything from his deportment to his manner of speaking was fascinating and since he never once broke character one can assume it was his normal habit. He quickly warmed to us his lone inquisitors that bleak day and expounded at length on this his beloved hobby, job and pastime. The house that Louis Braille lived in was right across from the office of the curator. Below is a bit of copied information I found on the internet that gives a better description than I could have.

As soon as he could walk, Braille spent time playing in his father's workshop. At the age of three, the child was toying with some of the tools, trying to make holes in a piece of leather with an awl. Squinting closely at the surface, he pressed down hard to drive the point in, and the awl glanced across the tough leather and struck him in one of his eyes. A local physician bound and patched the affected eye and even arranged for Braille to be met the next day in Paris by a surgeon, but no treatment could save the damaged organ. In agony, the young boy suffered for weeks as the wound became severely infected; an infection which then spread to his other eye, likely due to sympathetic ophthalmia.

Louis Braille survived the torment of the infection but by the age of five he was completely blind in both eyes. Due to his young age, Braille did not realize at first that he had lost his sight, and often asked why it was always dark. His parents made many efforts – quite uncommon for the era – to raise their youngest child in a normal fashion, and he prospered in their care. He learned to navigate the village and country paths with canes his father hewed for him, and he grew up seemingly at peace with his disability. Braille’s bright and creative mind impressed the local teachers and priests, and he was accommodated with higher education.

He excelled in his education and received scholarship to France's Royal Institute for Blind Youth. While still a student there, he began developing a system of tactile code that could allow blind people to read and write quickly and efficiently. Inspired by the military cryptography of Charles Barbier, Braille constructed a new method built specifically for the needs of the blind. He presented his work to his peers for the first time in 1824.

Entering the house we started in the kitchen. In the kitchen was a small stone sink with a drain that went outside to a barrel. This feature alone signified that the Brailles were a more well-to-do family in town. There was a big fire place, a table in the center of the room, and on the far side was his parents bed. Beside the bed to the right was a small narrow stairs going up to the loft where Louis and his siblings slept.

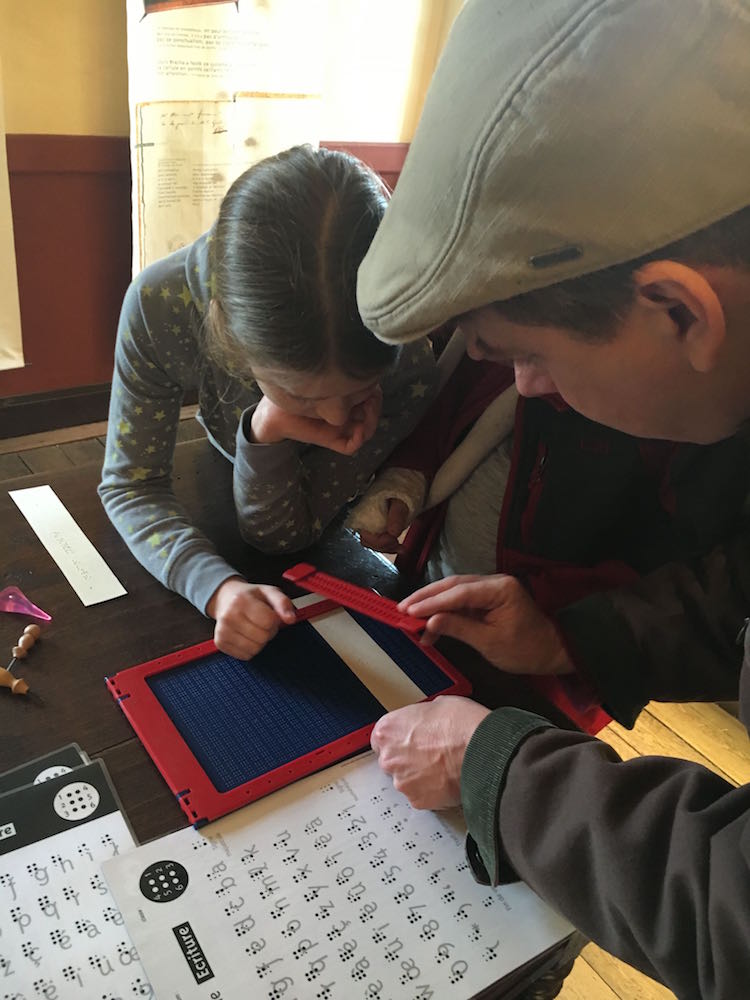

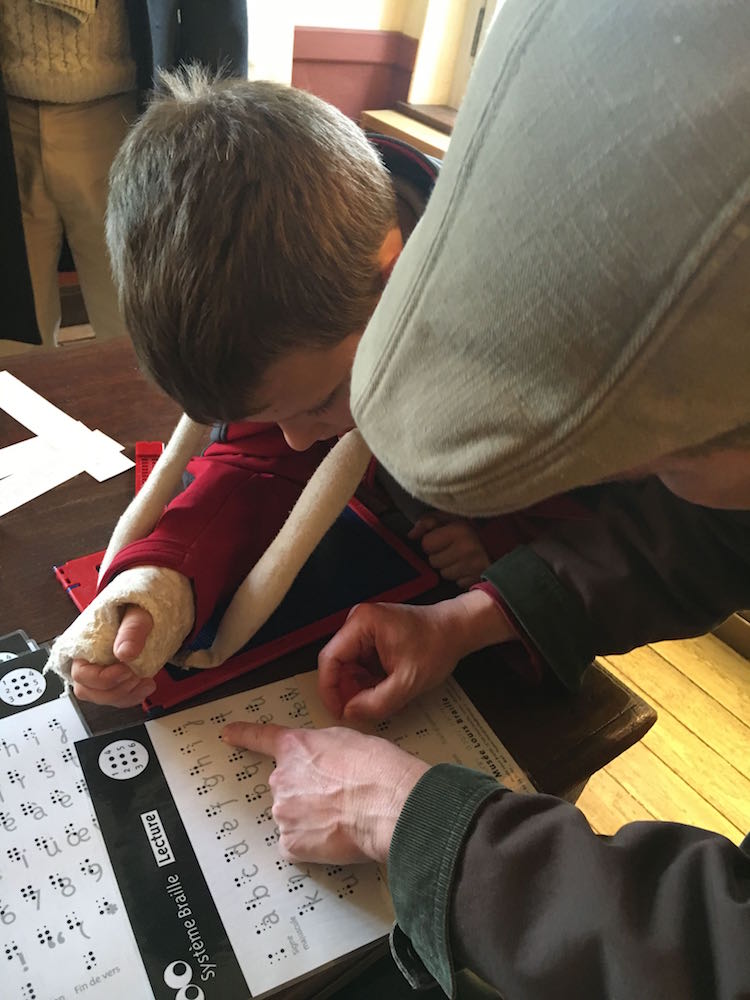

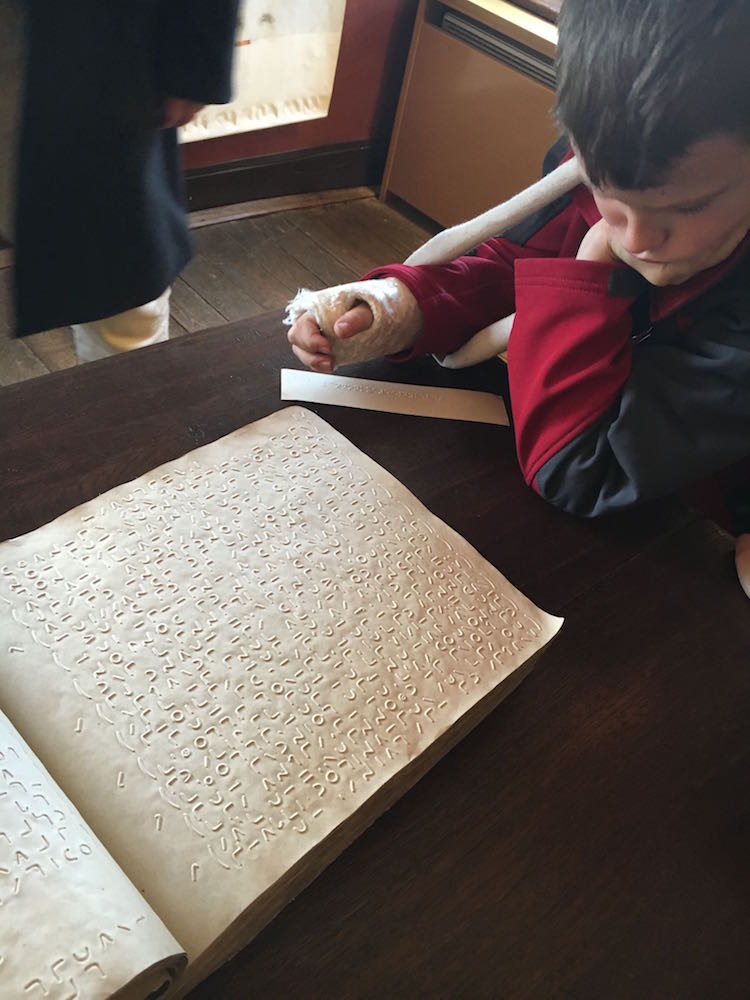

Back outside again we walked to Louis’s fathers workshop. Many old tools were there, and a couple pictures on the wall. His father made harness for horses in his workshop. Straight across from the door was a narrow stairs going up to the room where there were shelves of all the things Louis invented for blind people. There were games, books of braille, tools to punch paper to make the marks for braille, and a typewriter. In the center of the room was a table that we sat down at and the man let us try our hands at punching the paper. We all did our names, and he did the word Pennsylvania for us. You could not count to 8 before he was finished punching the letters out. It was fun to watch him do it. We were very slow doing our names. I still have my name in braille and the Pennsylvania paper.

When the tour was over we walked back up the hill and on the way we found a bright pink flower that was blooming. Back at the house we put the finishing touches on packing and cleaned. We then ate leftovers for dinner so we would not have to discard them. Dad was double checking our plane tickets and ascertaining what time we had to be at Charles De Gaulle Airport in Paris. Dad then sent us to bed around 8pm, because the next morning we had to be up at 6am.